In recent years, concerns regarding personal safety have fueled a significant surge in the popularity of trained protection dogs as a supplementary security measure. However, personal protection dog training remains a deeply misunderstood discipline, with many public assumptions shaped by cinematic tropes and exaggerated social media content. In reality, this specialized field focuses on stability, surgical control, and high-level decision-making rather than raw aggression. To truly appreciate how this training functions in real-world settings, one must look past the visual intensity and understand the psychological architecture required for a safe, reliable guardian.

Ultimately, protection training is not an appropriate path for every dog or every owner. It requires an exhaustive evaluation process, a long-term financial and temporal commitment, and highly ethical handling practices. This article provides an expansive look at how professional protection training is structured, why it prioritizes clarity over force, and why the owner’s responsibility is the most critical component of the equation.

1. The Strategic Purpose: Deterrence and Controlled Response

The primary objective of a personal protection dog (PPD) is rarely to engage in physical combat. Instead, professionals view these dogs as tools for deterrence and early warning. Consequently, a well-trained dog spends 99% of its life as a composed, neutral companion. Its presence alone often discourages potential threats, as most criminals prefer soft targets over individuals accompanied by an alert, focused canine.

When a situation escalates, the dog functions through two distinct modes of operation:

-

The Alert: On command or upon detecting a specific threat, the dog displays a powerful, vocal deterrent. This serves as a “stay back” signal, providing the handler with vital time to assess the situation or escape.

-

The Engagement: In the rarest of life-threatening scenarios, the dog engages physically. Importantly, this engagement is not a wild attack; it is a controlled bite on a specific target area, designed to neutralize the threat until the handler can safely depart or law enforcement arrives.

2. Temperament: The Essential Foundation

Selection is perhaps the most critical stage of the entire process. Furthermore, it is a common misconception that any “tough” dog can be a protection dog. In contrast, trainers seek out dogs that possess “nerve”—the ability to remain calm and analytical while under extreme pressure. A dog that reacts out of fear is a liability; therefore, trainers prioritize dogs that act out of confidence.

During the selection phase, experts evaluate several specific traits:

-

Environmental Soundness: Can the dog handle loud noises, slick floors, and chaotic crowds without losing focus?

-

Recovery Time: If a dog is startled, how quickly does it return to a neutral, calm state? Rapid recovery indicates the emotional resilience required for protection work.

-

Drive Balance: Trainers look for a harmonious blend of “Prey Drive” (the desire to chase and catch) and “Defense Drive” (the instinct to protect the pack).

3. The Supremacy of Elite Obedience

One cannot overstate the importance of obedience in this discipline. Because a protection dog possesses the capability to cause harm, the handler must maintain absolute control at all times. Specifically, obedience in the protection world is far more demanding than standard pet training. We refer to this as “Capping the Drive.”

A protection dog must respond to commands instantly, even when its adrenaline is peaking. For instance, if a dog is moving toward a threat, the handler must be able to “call them off” mid-stride. This level of reliability requires thousands of repetitions in diverse environments. If the obedience is not 100% reliable, the dog cannot safely progress to protection work.

4. Drive Channeling: From Play to Protection

Ethical protection training begins by utilizing the dog’s natural play instincts. Initially, the dog views the “bite sleeve” or the “tug toy” as a prize in a game. Trainers use this high-energy play to teach the dog how to use its mouth properly and how to enjoy the physical contest.

However, as the dog matures, the trainer introduces “conflict.” This is the point where the dog learns that the “decoy” (the person in the suit) represents a potential adversary. Through careful “drive channeling,” the trainer teaches the dog to switch from a playful state to a serious, defensive state. Moreover, the dog learns that it can only win this “conflict” by listening to the handler’s commands.

5. Environmental Neutrality and Real-World Conditioning

A dog that only performs well on a manicured training field is not a true protection dog. To address this, professional programs emphasize environmental conditioning. This involves taking the dog into the “polluted” environments of everyday life.

Handlers take their dogs into shopping centers, elevators, parking garages, and busy city streets. The goal is for the dog to ignore every person, dog, and distraction until a legitimate threat appears. Consequently, a high-tier protection dog is often the most well-behaved animal in any public space. They do not growl at the mail carrier or lung at fences because they have been taught that such things are not threats.

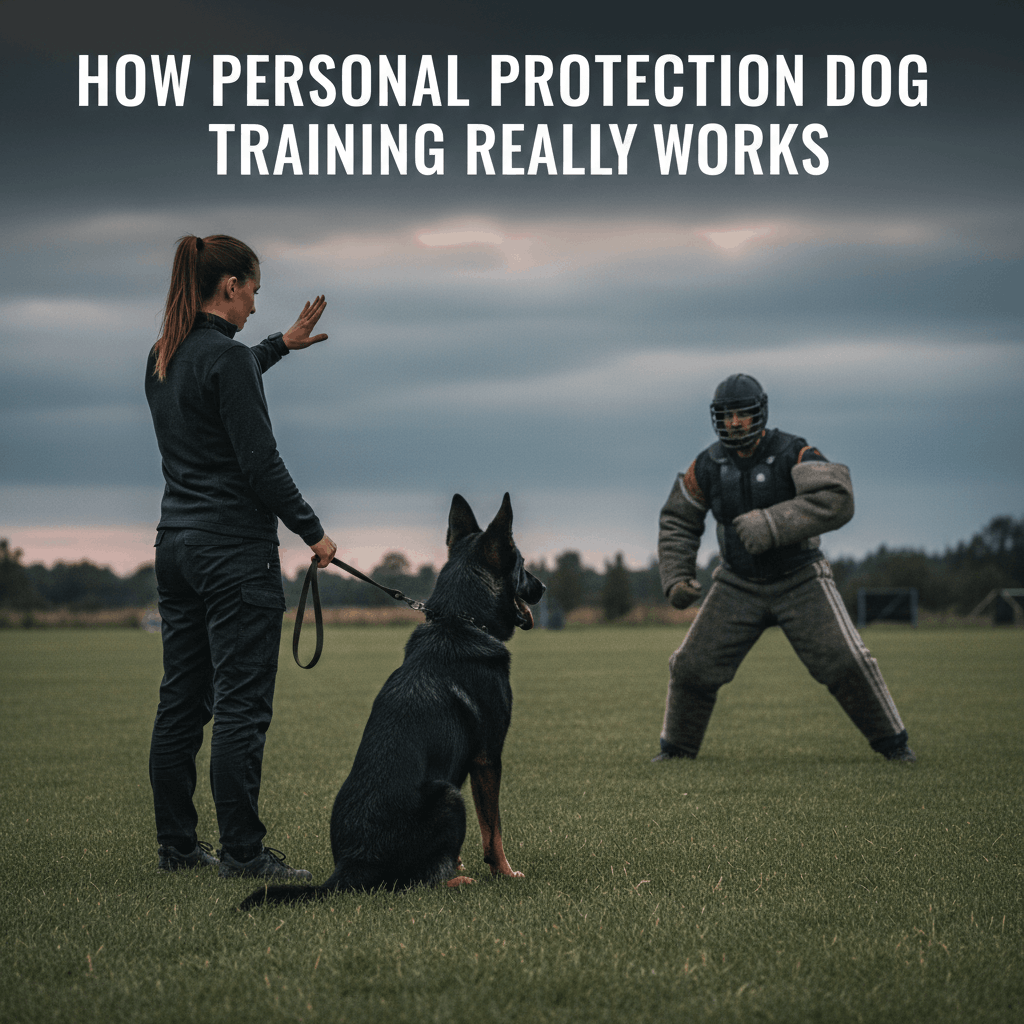

6. The Role of the Decoy: The Art of Controlled Stress

The “decoy” or “helper” is the person wearing the protective suit, but their job is much more complex than just being a target. Specifically, a skilled decoy acts as a teacher. They use their body language, voice, and movement to apply just enough pressure to build the dog’s confidence without breaking its spirit.

If a decoy applies too much pressure too soon, the dog may become fearful. Conversely, if there is no pressure, the dog will never learn to handle a real-life struggle. The decoy’s goal is to make the dog feel “ten feet tall.” By allowing the dog to “win” these controlled confrontations, the trainer builds an animal that will not back down when faced with a genuine predator.

7. Stress Management and Emotional Regulation

One of the most impressive aspects of modern PPD training is the dog’s ability to regulate its own emotions. During a training session, a dog’s heart rate may skyrocket as it prepares to defend its handler. However, the moment the exercise ends, the dog must be able to “switch off.”

Trainers achieve this through “re-set” exercises. After an intense engagement, the handler will ask the dog for a calm “sit” or a “down.” This teaches the dog that even in the heat of battle, they must remain tethered to their handler’s emotional state. This regulation prevents the dog from becoming “hyper-vigilant” or chronically stressed in the home.

8. Ethical Standards and Modern Methodology

In the past, some trainers used archaic, “compulsion-based” methods to create aggressive dogs. Fortunately, the industry has evolved. Today, the most respected trainers utilize Balanced Training, which focuses heavily on positive reinforcement, motivation, and clarity.

Ethical training ensures that the dog enjoys the work. When a dog views protection as a job it is successful at, it develops a deep bond of trust with the handler. Force-based training, on the other hand, creates instability. If a dog fears its handler, it will eventually project that fear onto the world, leading to dangerous and unpredictable behavior.

9. Legal and Social Responsibility

Owning a personal protection dog carries significant legal weight. In many jurisdictions, a dog with this level of training can be considered a “dangerous instrument” or even a weapon. Therefore, handlers must be fully aware of the laws regarding self-defense and canine liability.

Furthermore, social responsibility is paramount. A PPD owner must ensure that their dog is never a nuisance to the community. This means having secure fencing, using appropriate equipment in public, and never allowing the dog to “practice” on unsuspecting people. Professional trainers often spend as much time educating the human as they do training the canine.

10. The Maintenance Phase: A Lifetime Commitment

Protection training is not a “one and done” process. Instead, it is a perishable skill set that requires constant refinement. If a handler stops training for six months, the dog’s “clarity” will begin to fade. They may become slower to release a bite or less focused during obedience.

To maintain a high-level guardian, owners should participate in “maintenance sessions” at least twice a month. These sessions allow professional decoys to test the dog’s nerves and ensure the obedience remains sharp. Additionally, as a dog ages, the handler must adjust the physical demands of the work to protect the dog’s health and joint longevity.

11. Common Myths and Misconceptions

Several myths continue to haunt the protection dog industry, often leading to poor decision-making by prospective owners:

-

Myth 1: Protection dogs hate people. In truth, a good PPD loves people and is highly social. They only switch into “work mode” when directed.

-

Myth 2: You can train a “guard dog” in your backyard. Professional training requires specialized equipment and expert decoys. Amateur “agitation” training often leads to ruined temperaments.

-

Myth 3: These dogs are dangerous to children. When properly selected and raised, PPDs are exceptionally gentle with their family members, often showing a heightened level of tolerance for children’s antics.

12. Selecting the Right Partner

If you decide to pursue a protection dog, the choice of a trainer or kennel is your most important decision. You must look for transparency, a proven track record, and a focus on “real-world” testing rather than just sport scores. Ask to see the dog working in a public setting, and ensure the trainer emphasizes the “out” (the release) as much as the “bite.”

Conclusion

Personal protection dog training is a sophisticated discipline that centers on the pillars of control, stability, and ethical responsibility. It is fundamentally not about creating an aggressive animal, but about developing a clear-headed, restrained guardian that can navigate the complexities of modern human society. When executed correctly, this training enhances the safety of the household while preserving the psychological well-being of the dog.

Ultimately, the success of a protection dog depends on the strength of the human-canine bond. Through rigorous selection, elite obedience, and ongoing maintenance, these dogs become more than just a security measure—they become the ultimate partners in safety and companionship.